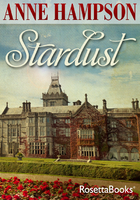

Abbot's Bromley, the country house belonging to Charles Dawson, Esq., a wealthy wholesale chemist from Stafford, is one of the handsomest and most comfortably furnished in the entire county, besides being wonderfully placed for scenery. It lies some seven miles from Stafford. Close by, rise the famous oaks of Bagot's Park, said to be the largest in England and perhaps in the world. Within walking distance you come upon Cannock Chase with its grassy slopes and great wealth of wild flowers, and Shoughborough Park with its banks of tall ferns. Abbot's Bromley also commands a view of Colnwich Nunnery, and of the swans reflected in the Trent's placid waters.

Charles Dawson, a robust and mellow-voiced widower in his sixties, has a fine eye for horseflesh, an epicure's taste in port, a connoisseur's knowledge of pictures, statuary, medals, et alia-and much to tell about the next stage in William Palmer's chequered career. The rest of this chapter will be related in his own words.

CHARLES DAWSON, ESQ., J.P.

Poor little Annie, how sadly we all miss her here! I did my best to cure her infatuation for that smooth-tongued young scamp-as much, I swear, as any loving guardian could have done-but she would not listen to me. She had set her heart on becoming Mrs Wm Palmer. I also quarrelled mortally on her account with my old friend Mr Thomas Weaver, the solicitor; nor have I since had reason to repent my attitude, the way things turned out. Far otherwise, indeed!

Let me begin at the beginning-though, I warn you, it's by no means a savoury story. One day, while I was still actively conducting my druggist's business at Stafford, a gentleman with trembling hands and a face as yellow as a guinea pushed open the shop door. I summed him up at once as an officer, attached to the East India Company's forces, who had ruined his constitution by persistent bouts of fever, over-exertion in the sweltering heat of the Bengalee Plains, and constant indulgence in the curree and chutney used by the native cooks to disguise the unpalatable taste of their goat's flesh and chicken. He asked whether we could furnish him with a certain foreign drug which one of the retail druggists of the town, to whom he had applied, ignorantly asserted did not exist. I attended to this customer personally, and produced a sample of the drug named; though counselling him in a friendly manner against its indiscriminate use. He then explained that it was recommended to him by an English physician in Bombay as strongly assisting the action of the liver. I told him, with what I hope was becoming modesty, that some druggists often know more about the action of drugs than do some physicians; and suggested another course of treatment as both less costly and more efficacious. A few days later the gentleman returned to thank me for my advice and, introducing himself as Colonel Brookes, late of the East India Company's service, asked me to do him the kindness of dining at his newly-purchased house in Front Street.

Colonel Brookes proved to be a reserved and gentle man, the veteran of many hard-fought campaigns against the Pindaries and Mahrattas. He was considerate, generous and wealthy, but unmarried and, though a Staffordshire man, had been so long absent from our shores as to have very few friends or acquaintances left in the county. I took a liking to the Colonel and presently introduced him to Dr Edward Knight, the most competent physician in Stafford, and old Mr Wright, the brewer; and we were very glad of him to make a fourth at short whist in our twice-weekly sessions, and thus fill the place vacated by the late Captain Browne, R.N., recently dead of an apoplexy. We found the Colonel to be a keen and skilful player, with a fine sense of sportsmanship, and though he never became our intimate in the rollicking style of poor Captain Browne, we congratulated ourselves on our acquisition. He opened his heart most fully to Dr Knight, with whom he discovered that he had been a fellow-scholar at the Grammar School some fifty years before, and who was married to a cousin of his. When Dr Knight inquired privately one day: 'Colonel, may I be permitted to ask a perhaps indiscreet question-why is it that you have never married?' he heaved a deep sigh and took fully a minute to answer.

Then he explained that he had been one of five brothers, of whom he was now the sole survivor. 'They each and all died by pistol shot,' he added.

'They were inveterate duellists, I suppose?' Dr Knight suggested.

The Colonel shook his head mournfully.

'Ah, so they fell in battle?' pursued Dr Knight.

Again a shake of the head. 'We Brookes are a melancholy breed, Sir,' the Colonel at last forced himself to say, 'and each of my brothers in turn, when the unhappiness of living this life out proved too great for him, blew out his own brains. That is the reason why I have never married; I cannot wish either to perpetuate the family taint of suicide by begetting children, or to bring disgrace on their mother. For though I have fought successfully against the temptation of self-murder all my life, and though its recurrence has become both less frequent and less violent with advancing age, I can never be sure that it will not one day leap upon me like a lurking tiger. Indeed, only the other evening…

Emotion prevented the Colonel from completing the sentence, but Dr Knight made him promise that if he ever felt a return of the evil, he would promise on his honour to call without delay at the surgery, whatever the hour, for consolation and friendly support. Colonel Brookes pledged him his word as a soldier, and appeared to be much heartened by the old Doctor's evident sympathy.

I had, by the way, also introduced Colonel Brookes to the Mr Thomas Weaver of whom I spoke just now: a competent solicitor, then entrusted with my own business affairs, who seemed willing enough to undertake the Colonel's. Mr Weaver advised him to buy a property in the town consisting of seventeen acres of land, valued at three to four hundred pounds the acre; also of nine fine dwelling houses at the back of St Mary's Church, the leases of which brought in a handsome income, or at least handsome in comparison with the purchase price. The largest of these had lately become unoccupied at the expiration of its lease.

Now, though Colonel Brookes was a model citizen in all other respects, chronic ill-health had blunted neither his sexual appetite nor his virility; and when he engaged a widow and her daughter to be, respectively, his cook and parlourmaid, trouble soon ensued. Disdaining the widow, a buxom woman of forty who had already set her cap at him, he made surreptitious love to the seventeen-year-old daughter who (let me be frank) failed to repel his advances with the firmness that might have been expected of a decent girl. The mother, returning from the market one day, caught the pair together in the parlour: the Colonel seated on the sofa, the girl mounted astride his bony knees, while his aged hands greedily explored her young bosom. Rage and jealousy did their work: the widow not only gave immediate notice, but demanded fifty guineas from him as the price of silence.

Their precipitate departure from the house, and the blushes of the daughter when questioned on it, gave rise to so much talk among neighbours and trades-people that the Colonel was hard pressed to find domestic service; for Stafford is not a large town. He therefore privately consulted Mr Weaver, making a clean breast of the affair and begging for his help. Mr Weaver hummed and hawed for a while before he ventured: 'Well, Colonel Brookes, I understand that you are not a marrying man, but that neither are you a monk, and I daresay during your stay in India you found little difficulty in assuaging…'

'No difficulty at all,' agreed the Colonel. 'Among the heathen Hindoos these matters are easily and cheaply arranged. And I have always liked young bed-fellows; the younger the better, let me confess.'

Mr Weaver hummed and hawed again. Then he came out with: 'Well, Sir, I am not a pander by profession, but now that you consult me as a friend in trouble… well, there's pretty Mary Ann Thornton, who was in great distress last year. Captain John Browne, of the Royal Navy, her employer… in short, he died suddenly, leaving her in the family way. However, since the child did not long survive its birth, no claim for maintenance was made on his estate, and Miss Thornton is at present unemployed. She has the reputation of being a hard worker, and appears to prefer mature men to her own contemporaries. She can't be a day above eighteen years old, with fair hair, blue eyes, and a good figure. May I send her along to your residence?'

The affair was thus arranged, and Mary Ann Thornton came to the Front Street house, bringing with her as cook an elderly aunt, whom the Colonel agreed to pay pretty high wages. Miss Thornton herself doubled the parts of housekeeper and concubine. The Colonel became passionately addicted to her company.

Well, Sir, men are men, and we of the Whist Club turned a blind eye to these domesticities, as being none of our business; especially after Dr Knight dropped a broad hint of why the Colonel shrank from marriage. 'And I am sure it is far better,' he said, 'that the Colonel should keep a healthy young mistress, than to be obliged to seek the doubtful solace of a bawdyhouse-his visits there would be not only dangerous, as exposing him to venereal infection, but also scandalous. We do not, I take it, wish to be known as persons who regularly associate with an old rake.'

We assented, though not without presentiment of some unhappy sequel. Miss Thornton soon came to realize the Colonel's increasing dependence on her services. She grew worldly and ambitious, and nothing would satisfy her save that 'he should make an honest woman of me,' as she put it, paradoxically enough. Yet he continued obdurate in his resolve to stay a bachelor, even when she announced her pregnancy. It has, by the bye, been said that a younger lover fathered the child; this is market gossip, though, and the Colonel at least believed himself responsible for her condition. I took the view that he could do worse than marry the girl, despite her gross ignorance and low birth. The former fault might have been remedied by private tuition; the latter would have been cancelled by the adoption of his name. He felt very tenderly towards her, that is certain, and made a solemn undertaking, in Mr Weaver's presence, not only to keep her in the style which she might have expected as a wife, but to remember her handsomely in his will. All her tears and pleadings, however, failed to shake his resolution not to marry. When he offered to arrange an abortion, if she so desired, she professed to be outraged, saying that this was crime both against the laws of England and against Nature. Until the very end of her confinement she cherished hopes for a change of heart in him, but all that he would do by way of placating her was to move from their somewhat cramped and public quarters in Front Street to the more commodious vacant house behind St Mary's Church, and furnish it regardless of expense. She suffered a difficult pregnancy, which made her behave in a very strange manner, casting the wildest threats at the Colonel. On one occasion (so he confided to Dr Knight) she snatched up a kitchen knife and chased him around the table. On another, when he went to his bedroom, shortly before dinner, he found her lying drunk on the floor, with an empty quartern bottle of gin tumbled beside her.

Nevertheless, the child, a girl, was born safe and sound. The Colonel felt lasting chagrin, since it had been to avoid the begetting of children that he had registered his vow; and Mary Ann Thornton, unappeasable resentment. Even if he now made her Mrs Brookes, that honour would come too late: the child was born illegitimate. She continued to drink heavily and, since the Colonel had guilty feelings in regard to her, tyrannized over him with impunity. The affair reached such a pitch that neither old Mr Wright, Dr Knight, nor myself dared call at his house for fear of witnessing disgraceful scenes. The blue-eyed belle was fast losing her looks, becoming thin and angular, with that blueish pallor which betrays a constant recourse to gin; and made no attempt to rule her excessively foul and vulgar tongue. She never ceased to blame him for 'whoring' her and, by his cruelty and neglect, driving her to the bottle.

The chief bone of contention between them now was the child, whom Miss (now Mrs) Thornton regarded with possessive greed, and on whom Colonel Brookes doted, for he loved the company of children. In better moods she encouraged his affection for little Annie, but when the gin was working in her, would roughly order him out of the nursery. 'This is my b-child,' she would scream. 'It could also have been yours, you toad, you turd, you Turk, if you had been the gentleman I first mistook you for! But you have cast a blight on the poor innocent's life by your refusal to lend her your name, and neither she nor I will ever forgive you. Now, go, go-out with you-before I tear your eyes from their sockets! And one word of protest-you b-you-and I'll dame you with these shears!'

She would then pick up the shears, or it might be a knife, or a cleaver, and my unhappy old friend would run for shelter to The Lamb and Flag. He even, on one occasion, took sanctuary in the vestry of St Mary's Church. Thus the scandal which Mr Weaver had hoped to avert, by his discreet pandering to the Colonel's weaknesses, grew a thousand times worse than if the unfortunate man had merely been known as a frequenter of bawdy-houses. He could, of course, have posted out of the county for his weekly pleasures; to Liverpool, for example, and little harm done. But now, when one of her ungovernable rages overcame her, she would follow him all the way to The Lamb and Flag-not fully clad neither, her hair in curling pins-where with her ramping, stamping, tearing and swearing, for all the world like a drunken Lifeguardsman, she would create a most horrible scene, finally catching him by the collar and hauling him off home. 'Poor gentleman,' some of the rough fellows who frequented The Lamb used to say na?vely, 'he might as well have been married!'

After long deliberation, we of the Whist Club decided not to exclude him from the twice-weekly sessions at my house, and thus add a last, and perhaps fatal, drop to his cup of bitterness; nor did the woman ever venture to pursue him there. I have since heard it said that these two evenings were sacred to amatory revenge; she had a lover, a bricklayer's labourer, whom she entertained in style during her protector's absence.

So it went on for some years, until the reign of the late King William-the year 1834, to be precise-when one morning Colonel Brookes was found dead in the parlour of his house, clad in dressing-gown, slippers and cap, with a bullet through his heart and a still smoking pistol lying on the carpet beside him. The old cook made the discovery. She had heard her niece's voice raised in a shriek of anger, which was followed by a cry of despair from the Colonel, and then a pistol shot. A moment later Mrs Thornton quitted the parlour in hysterics and, rushing upstairs, slammed and locked the bedroom door behind her. The cook at once hastened to summon Mr Weaver, who in turn sent post haste for Dr Knight; and the two of them-so soon as Dr Knight had satisfied himself that life was extinct-mounted the stairs to the bedroom and demanded that Mrs Thornton should come out and give them an account of this melancholy event. When she made no reply, Mr Weaver entered the room by way of the window-a ladder left by the painters affording him convenient and easy access to it. He snatched the gin bottle from Mrs Thornton's hands, and unlocked the door to admit Dr Knight.

Fortified by the spirits, Mrs Thornton agreed that she had had words with the Colonel, whom she reproached for his constant and unnatural demands on her services between the sheets; but swore, by all that she held most holy, that the cry overheard by her aunt was one of indignation, when he drew a pistol from beneath a sofa squab, pointed it at his heart, and warned her very coolly: 'If you utter one more word, I shall kill myself.' Then, inadvertently (they were told), she had uttered another word, or words, namely: 'For God's sake, don't! Think of the child!'-whereupon the Colonel pressed the trigger.

Dr Knight and Mr Weaver went pensively downstairs again. Unable to decide on the truth of the story, they came to ask my advice as a Justice of the Peace. In the absence of any witnesses other than the aunt, who was hard of hearing, and Mrs Thornton herself, the truth could never be exactly known; but Dr Knight pleaded that the child's future must, at any rate, be safeguarded. Little Annie was already proverbial in the neighbourhood for her simplicity, goodness of heart and gentle manners, and had become a leading scholar at St Mary's Sunday School. 'It is bad enough to be born out of wedlock,' said Dr Knight, 'it is worse to be the daughter of a suicide. And what girl in Christendom, however saintly, could face the world in the knowledge that her mother had committed murder?'

'How does the will run, my dear Sir,' I asked Mr Weaver, whom I still esteemed highly at that time.

'Well,' said he, 'all I know is that you two gentlemen are named as his executors. The Colonel drew the will himself last July-against my advice, because it's no easy matter for a layman to draw a sound will unassisted by a solicitor-and would not show me the document, but deposited it, sealed, in my safe.'

'Can you explain the hugger-mugger?' I asked.

'Well, Sir,' he answered, 'it may be that Mary Ann Thornton figures in the will, which made him ashamed to discuss her case with me. She has occasioned him much unhappiness of late years, and because I recommended her to him as his servant…'

'As his concubine, Sir,' I reminded him.

'For Heaven's sake, let me be! You'll be saying next that I charged a stud-groom's fee for the transaction.'

'You have earned it, at all events,' said I bitterly.

Mr Weaver then accompanied us to his office and unsealed the will in our presence. The Colonel had divided his property into two parts: the nine houses were to go to Mary Ann Thornton absolutely; a capital of some twenty thousand pounds, mainly in Sicca rupees, and the rents of the farm land (which might not be sold in her lifetime), were to be divided between Mary Ann Thornton and his daughter Ann Brookes, in the proportion of three parts to two. Dr Knight and I were also appointed guardians of the child, and charged to pay her only the interests of her fortune until she came of age or married, when she might receive the whole of it. The Colonel, however, insisted that the child must be taken from her mother, a confirmed drunkard, and brought up genteely.

We professed ourselves happy enough to comply with the testator's wishes, but Mr Weaver sighed as he said: 'This will is flawed. I fear it will be disputed.'

Disputed it was, by Mrs Thornton, who went to another solicitor for advice. While not objecting to the legacies, she was outraged by the Colonel's animadversions on her character and his attempt to rob her of Annie, whom he claimed as his own daughter; and vowed that she would fight the case in every court, low or high.

Meanwhile, she was in danger of the rope; for all Stafford knew her character and openly accused her of murder. A coroner's inquest could not be avoided. Dr Knight managed the business very well; he somehow contrived to bring Mrs Thornton to the inquest cold sober and decently garbed in widow's weeds. He also coached her into telling the same story she had told before, though omitting the scandalous part and altering the account of her quarrel with the Colonel. When she had done, Dr Knight himself gave evidence of the Colonel's confidences made him some years previously, as to why he would never marry, and mentioned the Colonel's promise to call upon him at the surgery if ever he felt the suicidal mania threatening him again.

The Coroner then asked: 'Dr Knight-pray remember that you are on your oath-did the Colonel in effect call upon you at the surgery, and did he warn you of the recurrence of his mania?'

Dr Knight replied: 'The answer, Mr Coroner, is both yes and no. He came, as I now believe, ready to make such a statement, and if he had done so, I should have taken immediate steps to place him under restraint, But he contented himself with hints, which I was too obtuse to grasp. He came calling at about five o'clock, and talked somewhat disjointedly; a condition characteristic of the malarial fever from which he suffered at regular intervals. I at once urged him to take the usual stiff dose of quinine. He promised that he would do so upon his return home; but before rising to go, he asked me: "Dr Knight, are you a Freemason?" I smiled as I answered: "If you were yourself a Mason, and if I were also a Mason, you would have already known me as your fellow by my manner of shaking hands on our first acquaintance; but if you are not a Mason, as I suppose must be the case, how can you expect me to reveal myself as one, if indeed I am? You must surely be aware that membership of the Order is a close secret."

'Colonel Brookes let that comment pass, and launched into a story. "I have just had very sad news from Liverpool," he said. "It concerns a friend of mine, the Captain of a fine East India-man, which makes a regular run between Liverpool and Bombay. I dined at his table every day, both when I returned to India in 1817, as a major, after a six months' convalescence; and again on my last voyage, when I sold out and came home to die among my own people. This Captain was a Freemason, and as conscientious in his loyalty, Dr Knight, as you seem to be. Well, one day he was aggrieved to find that his first mate had confided to a lady passenger some disquieting news about the soundness of the ship's rigging, and added: 'God knows, Madam, what our fate will be if we chance to run into foul weather off the Cape!' The lady's husband, a Madras merchant, ran in alarm to the Captain's cabin and demanded to know the facts of the matter. My friend reassured him that the rigging was sound-though, in truth, he had been forced by the owners to sail, on penalty of losing his command, despite his protests that 'the yards were rotten as damp straw.' The merchant having gone, my friend charged the first mate with spreading dangerous alarm and betraying nautical secrets. To which the mate replied, rudely laughing in his face: 'And I suppose, Captain, that you yourself have never betrayed any secret which you solemnly swore "to heal, conceal and never reveal"?'

'"At this reference to the Masonic oath, my friend looked up sharply, whereupon the first mate quoted to him certain prime Masonic secrets entrusted only to adepts of a high degree."'

The Coroner somewhat testily asked, at this point, whether the evidence was relevant.

'Pray have patience,' answered Dr Knight, 'and you will see that it is not only relevant, but crucial.' He proceeded: 'The Colonel then told me that his friend the Captain, knowing the first mate not to be a Mason, was both amazed and alarmed; but it came out that he had himself betrayed these secrets one night in a feverish delirium, when the first mate came to him for orders. He had the impudent officer put in irons, then returned to his cabin, and was found soon afterwards shot through the heart-clad in dressing-gown, slippers, and cap… This, Sir, was the end of the Colonel's story. He took his leave of me, and from the circumstance that his corpse was found the next morning similarly clad and similarly shot, my opinion is that you may, without the least compunction, bring in a verdict of suicide. If anyone is to blame it must be myself, for not insisting that he should take the quinine then and there in my surgery.'

The Coroner thanked Dr Knight for his frankness, confessed himself satisfied with the evidence, and 'suicide while under the delusive influence of a malarial fever' was the verdict returned by the jury. When I afterwards complimented Dr Knight on the fertility of his invention, he made no reply.

Mrs Thornton, as I have said, disputed the will in so far as it denied her a mother's natural rights. It was also disputed by a Mr Shallcross, who represented himself as Colonel Brookes's heir-at-law; he pleaded that the Colonel had not been of sound mind for the past three years, as large bequests to the drunken and sordid woman who made his existence a living hell sufficiently proved. The Court found that the Colonel had been of sound mind, save during his occasional bouts of malaria, and therefore had the right to bestow his property at pleasure. He had, however, wrongly described the child as 'Ann Brookes', and wrongly assumed the right to appoint guardians for her. Nevertheless, Mr Shallcross's evidence, and the testator's own considered opinion, made it apparent that the child stood in want of suitable protectors. The Court also ruled that the testamentary language was not sufficiently forcible to convey the estate to mother and child absolutely, but gave them only a life interest in it. At their decease, it must become the property of Mr Shallcross, or whoever else might then be the late Colonel's heir-at-law. The estate was therefore thrown into Chancery, the costs of the trial deducted from its value, and Ann Thornton made a ward in Chancery. The Court appointed Dr Knight and me her guardians, at the charge of the estate; and the Colonel's wishes were, in effect, respected-except that the value of the estate, after the lawyers had been satisfied, was whittled to less than a half, and that Annie's fortune now consisted solely of a two-hundred-pound life-annuity, purchased for her by us.

Well, as little Annie Thornton's guardian, and a married man, it was only natural that I should take her to live in my house, where I put her under the same governess as my own children. And let me tell you, Sir, that I never had a moment's cause to regret my action. That child was a paragon of virtue, and had not an enemy in the whole world. Though painfully sensible of her false position as an illegitimate child-even if one of independent means-and as being banished for her own good from the society of an ill-bred and dissipated mother, yet she trusted in the kindness of God; showing in all her looks and actions the profoundest gratitude to Dr Knight and myself for the care bestowed on her. We had no scruple in referring to her as 'Annie Brookes', and thus keeping alive in her mind the nobler part of her natural inheritance.

Soon after Annie's arrival in our house, my wife had the misfortune to be struck down by an incurable disease. Though still only a little girl, Annie insisted on acting as sick-nurse, and her intrinsic kindness of heart and constant vigilance by night as well as by day were something more than surprising. My poor wife's sufferings terminated six weeks later. Annie wept bitterly; and after a decent interval I married again, for the sake of my children. What I had done to deserve further chastening by Heaven, Heaven alone can say; but as the result of a fall on a slippery road, my new wife miscarried in the first year of our marriage; and the complications of this accident were also mortal in their effect. Once again Annie played the ministering angel, and was constantly at the sufferer's sick-bed; not only to administer medicine and perform the often distasteful duties of a nurse, but to give her spiritual consolation in the dark hours of the night when sleep was far, and pain unabating. Indeed, Annie combined three noble professions in those sad months: those of doctor, nurse and clergyman. She was reduced to a mere shadow, when my wife's death at last released her from these self-imposed tasks.

I did my best to restore Annie's spirits, as soon as the period of mourning ended, by arranging treats and excursions for the family; and little by little her natural gaiety returned. But Dr Knight and I agreed that the time had come when she must go to a finishing school; and we unluckily decided upon one recommended by his cousin, Dr Tylecote of Haywood-the medical man whose then assistant was none other than William Palmer.

Miss Bond's school enjoyed, and still enjoys, a high reputation for good schooling in all ladylike accomplishments-Annie learned to play the pianoforte there in a quite masterly way-and the girls were, it need hardly be added, under continuous surveillance. It happened once or twice, however, that Palmer, as Dr Tylecote's assistant, was sent to visit the school, when a girl had been overcome by a colic, or cut her finger, or suffered some other slight accident which lay within Palmer's limited powers to alleviate. On one occasion, the sufferer was Annie, and it appears that he treated a strained ligament in her ankle with such gentleness that she fell head over heels in love with him-though he had no suspicion of her feelings, being busily engaged at the time in an intrigue with a red-headed girl from Liverpool, the step-daughter of a local gardener. Moreover, Annie happened to be very advantageously seated in church, for her pew commanded Palmer's profile at a short distance, straight across the aisle.

My quarrel with Mr Weaver grew out of this unfortunate affair. His elder daughter had also been sent to Miss Bond's finishing school, and one day, in the course of general conversation, she chanced to reveal Annie's secret attachment to Palmer, for which the girls were teasing her unmercifully. Weaver mentally noted the fact and, when Palmer was about to inherit his seven thousand pounds, and asked him to arrange for their conveyance, brought it out. 'Do you want a wife, Mr Palmer?' asks he. 'For if you do, I can introduce you to a very pretty young girl with a snug little fortune. She's a ward in Chancery. Colonel Brookes, her father, left her eight thousand pounds, which gives her a secure income of two hundred pounds a year.'

'There is nothing I should like better,' says Palmer, 'but can you be sure that this beauty would look twice at me?'

'Indeed, I can,' Mr Weaver answers. 'She has fallen deep in love with you already. Annie Brookes is eighteen years old, and highly accomplished.'

Yet Mr Weaver was fully acquainted with the circumstances of Palmer's leaving his appointment in Liverpool, and of his ill-behaviour at Dr Tylecote's; and doubtless also of his profligate life while walking the wards in Stafford Infirmary. To encourage such a depraved young man to marry my Annie for her money was nothing short of criminal; and so I told him to his face.